Disease Management Clinical Decisions

Insomnia Care: An Integrated Approach

Michelle Drerup, PsyD

Case Presentation

This patient is a 48-year-old mother of four children aged 18, 15, 12, and 7. She presents with a complaint of chronic insomnia that causes fatigue and mental fogginess during the day. She has a nondemanding part-time job, and her main involvement is caring for her children. Her 15-year-old son has cystic fibrosis, and she often has to care for him during the night when he has unexpected flare-ups. Her other children function fairly independently. Her husband is supportive but involved with his work. She describes herself as a worrier.

Her normal bedtime is 11 pm with a desired wake-up time of 7 am. Her sleep latency can go from 30 to 60 minutes, and she often wakes during the night. When she goes to bed, she frequently is preoccupied with family problems, especially about her son with cystic fibrosis. Even when she is not focused on problems, her brain will not “shut off” and allow sleep to occur. This is a typical description of psychophysiological insomnia, in which the alarm system has been trained to be on edge during the night. During the day, she often feels sleepy. On nights that she gets adequate sleep, she feels good the following day.

To compensate for her lack of sleep, she tries to sleep later in the morning on days when her husband can take over the family responsibilities. She also tries to take daytime naps and, on quiet nights, goes to bed as early as 8 pm.

This patient clearly has some sleep issues that need assessed further, especially for the potential diagnosis of insomnia.

Question 1 of 9

What is the approximate rate of chronic insomnia in primary care patients?Correct answer: ≥ 30%

Discussion

Insomnia is one of the most common medical complaints, with incidence estimates that vary according to the population surveyed and the insomnia definition. The most generally accepted estimates of incidence in the general population come from studies showing that at least 30% of patients in primary care settings report chronic insomnia symptoms.1-5

Insomnia may be more common among individuals with a psychological vulnerability to the disorder. Variables associated with the onset of insomnia include a previous episode of insomnia, psychiatric disorders, a predisposition toward being more easily aroused from sleep, poorer self-rated health, and body pain.

Insomnia (ie, not sleeping) in the sleep disorders classification system6 refers to a patient’s general complaint about difficulties with sleeping when the patient wants to sleep. Chronic insomnia is defined as difficulty falling asleep, trouble maintaining sleep, or awakening too early 3 nights a week for 3 months; however, shorter-term problems with insomnia can also require clinical attention. (In children, there are also the categories of resistance to going to bed on appropriate schedule and difficulty sleeping without parent or caregiver intervention.) In past classifications, poor sleep quality was a core qualifier, but it no longer enables the diagnosis, even though poor sleep quality is a feature of insomnia.

The key diagnostic criteria of insomnia are the following:

- Patient has had sufficient opportunities to sleep (ie, it is not sleep restriction),

- The sleep period occurs during the night, and

- Results in impaired daytime function.

For daytime consequences, definitions list these self-reported criteria:

- Fatigue,

- Sense of sleepiness,

- Difficulty with concentration,

- Memory difficulties,

- Poor mood,

- Irritability,

- Behavioral problems of impaired social, occupational, or academic performance.

These daytime consequences document that the patient has a problem with sleep and that there is a functional impairment that makes it a disorder. Many people have limited or poor sleep and may have sleep dissatisfaction, but they do not experience daytime consequences that would make the sleep problem a formal disorder. Under current diagnostic criteria for insomnia, at least one self-reported daytime consequence is required. The diagnosis of insomnia is a clinical diagnosis. There are no laboratory studies that can confirm it as a diagnosis, although laboratory studies can confirm other sleep disorders.

A proper diagnostic evaluation requires obtaining a thorough sleep history to confirm that insomnia exists and to identify potentially contributing medical conditions, psychiatric illnesses, other sleep disorders, medications, or substance use (including caffeine overuse). Other confounding sleep disorders include snoring and sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome, nightmares, or circadian phase delay. Hence, the clinician’s first duties are to clarify the extent and nature of the sleeping problem more generally and to avoid prematurely focusing only on the insomnia complaint. In general, clinical insomnia should be diagnosed only after other causes of sleep disturbances have been ruled out or reasonably discounted.

After confirming that this patient meets the diagnostic criteria for chronic insomnia, you begin exploring for causal factors. You obtain a thorough sleep history and perform a physical examination to identify factors pertinent to the differential diagnosis of a sleep disorder, such as other sleep disorders, medical diseases, psychiatric illnesses, or use of medications or substances that are associated with her insomnia. Laboratory testing can help confirm other disorders that could be contributing to her insomnia.

Question 2 of 9

In designing treatment strategies for chronic insomnia (> 3 months), which general causal factors should be the main focus?Correct answer: Perpetuating and/or maintaining factors

Discussion

Both A and B are incorrect. Predisposing factors such as gender, age, and low socioeconomic status can affect the risk of insomnia but are rarely amenable to treatment. Precipitating causes of insomnia are ubiquitous factors that affect everyone. Some short bouts of insomnia are inevitable in life, so it is impractical to address precipitating causes preemptively.

Perpetuating, or sustaining, factors are those that create a chronic, nightly recurrent pattern of insomnia that overrides the normal physiological forces that govern sleep. For practitioners, the therapeutic focus is on the perpetuating causes of chronic insomnia that can be medically and behaviorally addressed. Sustaining causes can be related to pain or medication use, but they also can be related to neurophysiological habit patterns and adverse cognitive-behavioral habit patterns that sustain insomnia.

Perpetuating factors of insomnia include the following:

- Poor sleep practices,

- Myths or untrue beliefs about sleep,

- Lifestyle factors that negatively impact sleep,

- Anxiety and worry about falling and/or staying asleep, as well as worry about the impact of sleep loss on functioning

Insomnia treatment often involves a systemic, detailed examination of the patient to find the perpetuating factors maintaining the sleep problems. These factors can be thought of as “alarms” that are chronically present and that override the normal sleep control systems.

How one lives and works during the day affects nocturnal sleep, and nocturnal sleep quality affects daytime functioning. Studies in both rats and humans3,7 have documented that stimulating mental activities (eg, exploring a new environment, doing calculations) cause persistent neural activities during sleep in the brain regions that were active during wakefulness. Being able to deal with the stresses and strains experienced during wakefulness can degrade nighttime sleep length and sleep quality. Thus, how one manages daytime activities has a bearing on one’s sleep. Similarly, how one sleeps also has a bearing on one’s daytime function.

Understanding these perpetuating factors, as well as the physiological processes that govern sleep is critical for patients and healthcare providers in understanding treatment strategies for insomnia disorder.

Core sleep processes

Question 3 of 9

Which of the following physiological processes are the primary governors of sleep?- Sleep cycle process

- Homeostatic process (Process S)

- Circadian rhythms process (Process C)

- Process W

- Melatonin secretion process

Correct answer: 2 and 3

Discussion

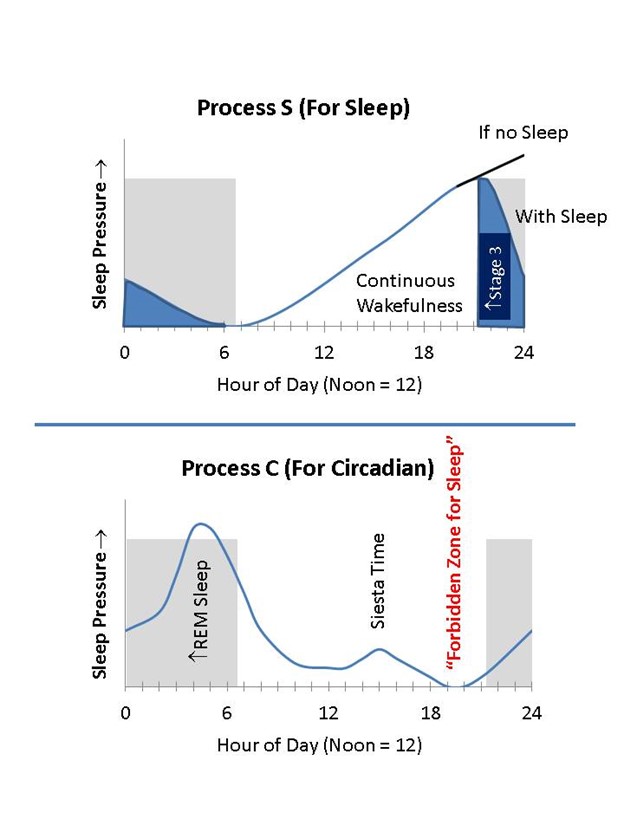

Process C and Process S are the main natural processes of sleep 8 that take priority in the understanding of sleep — especially for patients with insomnia. A goal of insomnia therapy is to have the patient work with, rather than against, these two core processes.

These processes are explained in the following graphs and text.

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Process C and Process S. The X-axis in the graphs shows the time of day in military time. The figures are idealized. There are minor person-to-person differences in these processes, but the general processes are extremely well established. These two processes are the main sleep-governing processes. They occur simultaneously and summatively, and they act mostly independently in governing sleep pressure and wake pressure.

Upper graph. Process S (homeostatic process) follows the principle that the longer one stays awake, the greater the pressure for sleep. This sleep pressure builds up slowly during continued wakefulness (or limited/fragmented sleep), but it can be rapidly dissipated with napping. It is believed to be caused by the build-up of adenosine in the extracellular space surrounding the ventrolateral preoptic (VLPO) neurons. Caffeine, an adenosine antagonist, probably maintains wakefulness by antagonizing the signaling effects of adenosine on VLPO neurons. Process S especially concerns the likelihood of developing greater delta-band waveforms during initial sleep, which is believed to be the most important for somatic and brain restoration. Chemically- induced (say from sleeping pills) delta sleep may not share the same characteristics. Natural delta sleep tends to occur more in the beginning hours of sleep and is thought to be related to sleep pressure arising from Process S.

Lower graph. Process C (circadian rhythm) is governed by the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in its role as the body’s master clock that coordinates in situ organ-specific clocks to control the physiological processes during various times of the day and night. Recent molecular biology has established that most organ systems have their own independent molecular circadian clocks, which are set and regulated by the SCN in order to temporally coordinate metabolic activities. The SCN clock mechanism is best set by bright light at dawn and, to a lesser extent, by melatonin secretion around dusk. Any variable time setting of the SCN by inconsistent time cues from the environment (especially light to the retina) may affect organ “slave” clock synchronization, thereby leading to physiological miscoordination that resembles that of jet lag.

Sleep pressure from Process C is normally greatest from 3 to 5 am, making this time the riskiest time for transportation and industrial accidents due to sleepiness. A lesser pressure toward sleep also arises in the midafternoon. Wake pressure from process C increases in the morning hours, has a small slackening in the afternoon, then wake pressure has a strong and seemingly paradoxical increase around 8 pm. This early evening period of wake pressure from Process C is called the forbidden zone of sleep.

It is diagnostically and therapeutically important to note that Process C and Process S do not follow common sense rules. Common sense might suggest that if you are not getting enough sleep at night, you can compensate with daytime naps or early bedtimes. However, naps lead to a loss of sleep-pressure buildup from Process S and early bedtimes lead to sleep attempts at a time when Process C is pushing one toward wakefulness. Rather than carrying out what common sense might tell them, patients with insomnia need to learn to accommodate these two natural processes governing sleep propensity.

Because of the central diagnostic importance of Processes C and S in assessing a sleep problem, there are two features of how a clinician can assess a sleep complaint.

- Being aware of Processes C and S when asking patients about their sleep, as this is a key foundation of clinical reasoning in sleep medicine.

- Routinely asking about time-based sleep parameters. Parameters to establish are the following:

- When does the patient physically go to bed (realizing that this can vary from weeknights to weekends)? Also, is the patient a shift worker?

- How long does it take the patient to fall asleep when he/she wants to sleep?

- When do middle-of-night awakenings occur, what causes them, and how long are they?

- When does the patient wake up in the morning?

- When does the patient get out of bed?

- Do naps occur (for any reason), when do they occur, and how long are they?

- How many hours does the patient sleep in a 24-hour period, naps included?

Sleep parameters may not be of interest to the patient because they relate only to their symptoms or suffering. For the physician, however, knowing the patient’s sleep parameters is essential to accurately diagnose a sleep disorder, and they provide additional data about the patient’s nighttime pattern that will enhance the treatment plan specificity and individually.

The three approaches this patient has used to get more sleep — sleeping in late, taking daytime naps, and going to bed early — seem to be common sense approaches; however, each opposes a primary sleep process and, thus, is counterproductive.

In the following questions, select the primary sleep process that the practice opposes.

Question 4 of 9

Sleeping in lateCorrect answer: A

Discussion

Sleeping in late. Not having a fixed sleeping schedule may give the patient’s suprachiasmatic nucleus a confusing signal for timing and coordinating the daily physiological processes of her body and mind. With a miscoordinated organ clock, fatigue and fogginess are more likely. A fluctuation in sleep schedule can amount to jet lag without actual jet travel.

The three approaches this patient has used to get more sleep — sleeping in late, taking daytime naps, and going to bed early — seem to be common sense approaches; however, each opposes a primary sleep process and, thus, is counterproductive.

In the following questions, select the primary sleep process that the practice opposes.

Question 5 of 9

Taking napsCorrect answer: Process S

Discussion

Taking naps. Napping can rapidly dissipate accumulated sleep pressure from Process S. If the patient had accumulated more Process S sleep pressure, her sleep at night would more likely be deeper, and she would be more likely to fall asleep at bedtime.

The three approaches this patient has used to get more sleep — sleeping in late, taking daytime naps, and going to bed early — seem to be common sense approaches; however, each opposes a primary sleep process and, thus, is counterproductive.

In the following questions, select the primary sleep process that the practice opposes.

Question 6 of 9

Going to bed earlyCorrect answer: Process C

Discussion

Going to bed early. This practice goes directly against the Process C forbidden zone of sleep — the early evening period of wake pressure that occurs around 8 pm.

Processes C and S are the “laws of gravity” when it comes to sleep. Knowledge about these processes should be taught in high school as part of normal health education, but it is not commonly provided. Health care providers need to provide this education to patients so they can better understand why therapeutic suggestions are made. Some people can play around with sleep scheduling and still get adequate sleep, especially during adolescence when sleep pressure remains high, but patients with insomnia are more likely to experience the consequences of ignoring these processes. Aging makes these two processes even more frail, but they are still in force until severe neurodegenerative conditions tear down the nuclei and connections that support these normally robust processes. Other life circumstances might act similarly.

The patient tries relaxing before bedtime and going without naps, but her sleep problems do not improve. She assumes that she has brain abnormalities, and that her only treatment alternative is to take sleeping pills, which would override whatever is wrong with her nerves.

Our initial examination found that she does not have hyperthyroidism, use glucocorticoids, or have any obvious medical cause of insomnia. Her noting that she feels well on days after she gets good nights of sleep is fairly typical of patients with primary chronic insomnia, and it is diagnostically distinctive. Also distinctive is that she may not be able to nap, even though she feels sleepy during the day and may want to nap. There are no data from direct tests or brain images that will determine any physiological cause of her insomnia.

This patient’s self-perceived views about sleep combined with her lack of knowledge about Processes C and S have led to her emotionally driven reasoning that assumes fateful certainties about her sleep. In turn, this type of hypochondriasis has maintained her insomnia.

Question 7 of 9

At this point, should the patient be referred for a sleep study?Correct answer: No

Discussion

In any initial evaluation, a standard sleep study (polysomnography) should be ordered if symptoms strongly suggest sleep apnea, periodic limb movement disorders, a nocturnal seizure disorder (requires electroencephalography), or a parasomnia such as sleep walking or rapid-eye movement (REM) behavior disorder. However, it should not be ordered if psychophysiological insomnia is the initial working diagnosis. Additionally, as recommended by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, a sleep study can be considered if the insomnia does not respond to initial treatments, including patient education and behavior-based therapy, over a course of several months.9,10 In this patient, a sleep study should not be ordered given symptoms are not suggestive of the above possible diagnoses and since the patient has not received any therapeutic interventions yet.

Treatment options for insomnia

Question 8 of 9

According to the American College of Physicians guidelines for the treatment of insomnia disorder, 11 what would be the recommended first-line treatment for this patient?Correct answer: Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia

Discussion

Cognitive behavioral-based treatments for insomnia (CBT-I) are ethically preferred. However, creating a sleep treatment strategy for a particular individual patient can rely on a balance between use of sleep medications and CBT-I. Before initiating insomnia-specific therapy, it is important to first treat any medical condition, psychiatric illness, substance abuse, or sleep disorder that may be precipitating or exacerbating the insomnia. Removing these other influences first may be better than adding another medication to their regimen. For example, treating obvious sleep apnea co-occurring with insomnia will often come first because the sympathetic activation brought on by the sleep apnea may be a partial cause of the inability to sleep. In this situation, not treating the sleep apnea first may be therapeutically inefficient.

Sleep-inducing medications are designed to amplify Processes S and/or help with the timing of Process C. Practitioners need to educate patients about these processes, the effects of sleep medications, and about going to bed later in the evening but only when they start to feel naturally sleepy.

Correct answer: Antidepressants at standard antidepressant-dose levels

Discussion

Several pharmaceutical agents have FDA-approved indications for the treatment of insomnia. The most commonly used are benzodiazepines and benzodiazepine-receptor agonists. These medications lengthen the duration of gamma-aminobutyric acid signaling in the thalamus and elsewhere in the brain. Also approved are melatonin agonists, which act similarly to how native melatonin from the pineal gland acts on melatonin receptors. Newer FDA-approved medications are low-dose doxepin (a tricyclic with antihistamine action at low dose) and suvorexant (Belsomra; an orexin/hypocretin antagonist). The loss of hypocretin-releasing cells causes type 1 narcolepsy, so the antagonism works like having a bit of narcolepsy. Diphenhydramine and other H1 antagonists have been FDA approved for over-the-counter use since the 1950s. These medications have been shown to improve sleep duration and sleep quality in randomized clinical trials, but they may not work for a given patient.

Although extremely rare cases of addiction developing uniquely from benzodiazepine and benzodiazepine-receptor agonists have been reported, this risk is minimal if patients with prior drug abuse are apprised, medications are appropriately administered, and mindful follow-up occurs. Dependence for sleep can occur, but this is usually not medically or psychiatrically dangerous and may be a conscious and ethical preference of some patients.12-14 However, most patients prefer behaviorally based treatments.15,16 If well-qualified behavioral sleep medicine specialists are not available, patients with more routine difficulties may benefit from using an on-line program developed by behavioral sleep experts (Cleveland Clinic’s program is called Go! to Sleep.) Neither CBT-I nor medications should be considered morally wrong, even though the behavioral-based treatments are medically preferred.

Common side effects to nonbenzodiazepine agents include drowsiness, dizziness, fatigue, dry mouth, and weight gain. Benzodiazepine medications can increase the risk of falls in elderly patients, an important consideration in those already at risk for hip fractures. However, the cause of dizziness, feeling drowsy or fatigued, or falls is complicated because insomnia itself can be the cause of these feelings, falls, and even daytime accidents, according to some epidemiological studies. Memory dysfunction can occur for many agents. Monitoring for these risks obviously is more important in frail patients, particularly those of advanced age or those taking complex medication regimens for other conditions. Importantly, use of benzodiazepine-receptor agonists (eg, zolpidem, zaleplon, eszopiclone, other benzodiazepines) are generally considered to be relatively contraindicated in patients with drug-abuse history that involves sedative-hypnotics or alcohol.

Antidepressants (eg, trazodone, amitriptyline, lower-dose mirtazapine) are not FDA-approved for insomnia but are widely used off-label for their sleep-promoting effects. When taken at bedtime, results generally have been positive; however, the routine use of sedating antidepressants to treat insomnia in patients who are not depressed is not officially recommended, in part because they have side effects that benzodiazepines do not have.14,17 Furthermore, antidepressants have not undergone comprehensive study in randomized placebo-controlled trials, leading to a lack of formal data on their efficacy and side effects. This is primarily due to a lack of financial incentives for manufacturers who did not pursue FDA approval for insomnia because clinical practitioners were using these agents off-label for insomnia.

Even though antidepressants do not have specific FDA approval for treating insomnia, their receptor profiles and modes of action provide benefits to many patients with sleep problems. For example, a patient with prominent anxiety as a symptom may benefit from the use of a serotonin-specific reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) for sleep insofar as the anxiety symptoms affect the patient’s ability to sleep. Some antidepressants (eg, amitriptyline, mirtazapine, doxepin) have multiple receptor actions, which may address anxiety or depression symptoms more directly, while those with an antihistamine action have an additional sedative effect. These antidepressant and antianxiety effects may occur even when the patient is taking the medications at times other than bedtime.

Most over-the-counter sleep aids contain diphenhydramine, an antihistamine that causes drowsiness. Evidence that diphenhydramine improves insomnia is rather limited and based on older, lower-quality studies. It commonly causes sedation the next day because of its long half-life, as well as weight gain. Slightly better-conducted studies suggest that doses larger than 50 mg only cause more side effects and not more sleep.

Quetiapine and olanzapine in lower dosing than for psychosis have been used for sleep at bedtime, as they have sedative side effects. However, these agents are best reserved for patients who have psychotic symptoms that would also be treated by these agents.

Benzodiazepine-receptor agonists have efficacy, but they can lose effectiveness in patients with long term use Longer-term effectiveness is likely to be patient-specific and medication-specific, which is true even for nonbenzodiazepines. This loss of efficacy happens for many agents used to aid sleep. This is an additional reason for encouraging follow-up with any medication-based treatment for insomnia.

Acute overdosing is also a concern, particularly if the patient is obsessed with sleeping, and it may be the most lethal risk for insomnia patients. Taking too many or the wrong medications for sleep can cause respiratory depression and death. Our patient has no substance-abuse history and is not desperate for sleep, so the likelihood of overdose or addiction is minimal.

A paradox that may occur is that any sleep medication can awaken the patient, much in the same way that alcohol may sometimes give the effect of causing activation or arousal.

In this case, since the patient had already attempted some behavioral strategies without benefit, a 1-month supply of zolpidem was prescribed with 1-month follow-up to determine her sleep outcomes. She also was referred for CBT-I to help her move away from the self-perception that every option has been tried toward understanding the long-term sleep management principles that provide predictable benefits to many people. Self-management skills can help treat chronic insomnia and prevent future transient insomnia from becoming chronic.

Clinicians need to avoid conveying messages or behaviors that might be interpreted as therapeutic abandonment, which is likely to increase the patient’s fear and tension about sleeping and exacerbate insomnia. This mental process drives insomnia in many cases. Thus, care of the insomnia patient involves conveying a concerned, ongoing commitment to addressing his or her insomnia — even if the insomnia seems impossible to treat.

Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia is a multi-component strategy that includes hygiene education, sleep logging, stimulus control, relaxation training, sleep restriction therapy, and cognitive restructuring. This approach focuses on structured behavioral and procedural approaches rather than unstructured psychological explorations. Patients selected for CBT-I need to be committed to this intervention and have the cognitive and emotional capacities to complete the homework assignments that CBT-I requires. Behavioral therapies have decisively been shown to improve daytime function and quality of life while reducing comorbidities in psychologically appropriate patients, even in patients with medical comorbidities. Side effects are not a long-term concern, but CBT-I administration is more time intensive and initially more costly.

In addition, CBT-I practitioners are required to have training and experience with various methods for intervening with chronic insomnia patients, including treating other somatic and psychiatric syndromes. However, few CBT-I specialists exist, and most are located in large metropolitan areas. Fortunately, the availability of telehealth/virtual visits have expanded availability of this treatment. In addition, for highly motivated and technologically savvy patients, internet/web based programs are available. If the patient uses a valid internet program, they should be advised that the instructions about changing sleep behaviors should be rigorously followed for several weeks. The benefits from CBT-I can be long lasting, but they usually do not appear for several weeks or longer.

Improvements from behavioral treatments frequently come from strategies aimed at decreasing physiological and mental arousal at night and re-conditioning the bed to be associated with sleep instead of distress and sleeplessness. A well-trained CBT-I practitioner has special skills in examining patients’ sleep pattern, behaviors, and cognitions. However, there are internet-based behaviorally based interventions that provide effective generic instructions for many patients.

Sleep medications, which some practitioners view as a medical evil, can provide an effective, fast-acting therapy to “smash” nighttime thinking — but only in a few patients. Sleep medications are best thought of as helping the two processes of sleep rather than smashing worries and wakefulness. Furthermore, sleep medications may not work over time, so behavioral treatments are usually preferable. Working to change a patient’s adverse sleep-associated habits will take more time than prompt-acting sleep medications, but using CBT-I to successfully change the adverse behavioral processes produces more durable and predictable sleep benefits for many patients.

We tried two drug therapies. Zolpidem, a nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic, helped with her sleep onset but not sleep maintenance. Eszopiclone, another nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic, was not as helpful for sleep onset but was better for her sleep maintenance; however, she had unacceptable metallic taste (a side effect in 30% of eszopiclone users) and was switched to two off-label drugs: clonazepam (benzodiazepine) and trazodone (tetracyclic antidepressant).

Although the drug combination was effective, she experienced daytime sedation. Doxepin, a tricyclic antidepressant, was started at a low dose (6 mg at bedtime), which may have antidepressant effects in a few patients but generally causes fewer side effects than a full dose for depression (300 mg). The low-dose doxepin helped her symptoms, but she experienced a feeling of excessive daytime sleepiness (but not the ability to nap!) and dry mouth that she was not able to tolerate.

At this point, a polysomnogram was ordered to help rule out occult sleep apnea or periodic limb movement disorder as contributory causes of her insomnia. A polysomnogram is appropriate because we had tried some interventions without success, increasing the likelihood that other occult causes of her insomnia (eg, sleep apnea) may be interfering with sleep. Most sleep medicine practitioners prefer that polysomnography be undertaken only if cognitive-behavioral interventions were ineffective or infeasible.

Results showed that the patient slept for 5 hours overall with a sleep efficiency of 75% (5 hours sleep divided by 6.7 hours in bed) and a wake-after-sleep onset of 1 hour. She had an overall apnea-hypopnea index of 3.5 events per hour, within the normal range of less than 5 events per hour. She had no periodic limb movements.

She was referred to a sleep psychiatrist, whose evaluation found some depressive symptoms. Escitalopram, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) was started at 10 mg/day. Patients with chronic insomnia may improve on an SSRI alone, if the insomnia is related to anxiety-related symptoms. Lessening anxiety symptoms often enables patients to fall asleep easier.

It is important for practitioners to remain open-minded about a patient’s diagnoses and therapeutic options. Do not assume that all patients who cannot sleep are depressed. In many cases, patients just cannot sleep. Although an antidepressant may improve their symptoms, it does not automatically mean they are depressed. Epidemiologically, there is a broad spectrum of clinical problems that spans depression, anxiety, and chronic insomnia, and patients often do not fit into convenient diagnostic categories. The causes of chronic insomnia are not fully understood; thus, it is advisable to try various approaches and options when treating a patient with chronic insomnia.

In this case, a behavioral treatment approach was initiated that included education about Processes C and S and their importance for sleep. The patient was also instructed on the importance of keeping a sleep log and how to avoid nocturnal clockwatching, which commonly contributes to patients remaining awake at night. To stabilize her biological clock, she was given a fixed time in the morning to be out of bed — even if she had not slept during the night.

She also underwent stimulus control therapy. This is a CBT-I strategy based on the idea that the sleep brain needs to be retrained to associate the bed only with sleep (or, for completeness, sex). Unfortunately, when a patient is awake for prolonged periods in bed, the sleep brain may “infer” that it is normal to be awake in bed. The instruction about stimulus-control procedures is that if one is persistently awake in bed, then he or she should get out of bed in dim light and do quiet, boring tasks (eg, reading the phone book) until feeling sleepy, and return to the bed only then. This habit discipline fosters the return of a normal sleep pattern. Research suggests at least a moderate (50%) but predictable benefit from using stimulus-control therapy.17-18

After 2 weeks, the patient’s sleep logging, bedtime scheduling, and stimulus-control procedures proved helpful. Additional approaches were started including relaxation training and a critical investigation of her thinking about sleep and insomnia. In the subsequent weeks, she continued to see improvement in her sleep and asked to eliminate her escitalopram use. During the next few months, the dose was reduced then eliminated. During this time, she also learned some coping skills to deal with the chronic strain and worry about caring for her son, so that it did not affect her as much. She also initiated management strategies to help control her son’s nighttime events. She continued to have substantially improved sleep, which improved her mood, and she reported feeling better during the day.

Conclusion

In this case, a variety of causes contributed to her chronic insomnia, and a variety of therapeutic interventions contributed to her improvement. This is common in patients with chronic insomnia. Hence, it is important to encourage patients to acquire physiologically accurate knowledge about sleep and to encourage practitioners to have an open mind when diagnosing and treating these patients. To avoid unnecessary worsening of insomnia, practitioners need to provide calm clinical support as the patient proceeds through various phases of assessment and treatment.

KEY POINTS

This insomnia case report focuses on the definition, causes, diagnosis, and treatment of insomnia. It reviews the following key points:

- The two main forces governing normal sleep are Process C (circadian rhythm) and Process S (homeostatic process).

- Chronic insomnia is associated with daytime consequences to patients’ health.

- Polysomnography does not provide accurate differential diagnostic information for most patients with chronic insomnia.

- Prescription sleep medications have efficacy but are associated with side effects and a risk of continued need of the medication for sleep.

- Cognitive behavioral treatments should be part of a comprehensive insomnia treatment plan.