Dermatology for Primary Care Physicians

Case 1

A 78-year old male with a past medical history notable for hypertension, Type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease (stage II), Parkinson’s disease, and coronary artery disease presents for evaluation of pruritus and hive-like lesions on his abdomen and thighs (see Figure 1). He otherwise feels well. The patient denies a history of urticaria, and reports these hive-like lesions have been constant over the past several weeks despite daily antihistamine use. Additionally, he reports individual urticarial lesions remain fixed and do not resolve within 24 hours.

Figure 1

What is the most likely diagnosis?

- Urticarial vasculitis

- Bullous pemphigoid

- Allergic contact dermatitis

- Mastocytosis

- Urticaria

| Previous | Next |

Correct! Answer:

Rationale

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is the most common of the autoimmune bullous disorders, with an estimated incidence of 10 to 43 per million people per year.1 Classically, its clinical presentation consists of tense bullae on an erythematous base in addition to marked pruritus, although urticarial lesions can predominate as well (urticarial-phase BP).2 It most commonly affects the elderly population, with reports demonstrating a significant increase in incidence after the age of 70 years, with a maximal incidence after 90 years.3

Urticarial vasculitis presents with urticarial lesions that often have a purpuric quality and typically lack associated pruritus. While allergic contact dermatitis is often significantly pruritic, its lesions tend to be eczematous (thin erythematous plaques with scale and serous crust) rather than urticarial in appearance, and its distribution should correlate with a specific pattern of exposure rather than the random distribution seen above. Cutaneous mastocytosis is more commonly seen in the pediatric population, with adult involvement more frequently seen in the setting of systemic disease. Mastocytosis presents with red-brown macules or papules that urticate after rubbing the lesions themselves. Finally, in urticaria, while daily antihistamines are not always sufficient, individual lesions themselves should last less than 24 hours.4

| Previous | Continue |

Case Continued

Given that bullous pemphigoid can sometimes be triggered by exposure to medications, you ask the patient what medications he takes and when each one was initiated.

Which commonly used medications have been implicated in drug-induced forms of bullous pemphigoid?

- PD-1 inhibitors

- Enalapril

- Vildagliptin

- Furosemide

- All of the above

| Previous | Next |

Correct! Answer:

Rationale

A recent review of drug-induced bullous pemphigoid (DIBP) found that nearly 90 medications have been implicated in causing this entity, with the strongest evidence for gliptin medications and, increasingly, PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors.5 Although the clinical and histologic features of idiopathic and DIBP share many overlapping features, a high degree of suspicion should remain if the eruption begins within three months of initiating a new systemic medication, particularly if previously associated with BP. Other features which have been described in DIBP include a younger age of onset compared with classic BP and marked peripheral eosinophilia.6

Two variants of DIBP have been described in the literature: one responding to prompt withdrawal of the offending agent and the second following a more persistent disease course despite withdrawal. As such, discontinuation of the suspected medication trigger is recommended when possible, as failure to recognize DIBP has been reported to lead to significantly longer courses of immunosuppression compared with recognized cases.7 However, in cases of DIBP triggered by PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors, close collaboration with oncology is recommended to attempt treating the BP and continuing the immunotherapy given these medications are often patients’ best hopes of controlling advanced malignancies.

| Previous | Continue |

Case Continued

The patient does not report taking medications that have been found to cause bullous pemphigoid, nor did he start any medications within three months of the onset of his rash. You do note that he has numerous comorbid diseases.

Which of this patient’s comorbidities has been most strongly associated with the development of bullous pemphigoid?

- Parkinson’s disease

- Coronary artery disease

- Diabetes mellitus

- Hypertension

- Chronic kidney disease

| Previous | Next |

Correct! Answer:

Rationale

Numerous studies to date have confirmed the epidemiological association between bullous pemphigoid and neurologic disorders including Parkinson’s disease, dementia, stroke, and demyelinating disorders.8,9,10 It has been hypothesized that CNS inflammation related to certain neurologic disorders leads to development of antibodies that display cross-reactivity to antigens in the skin, as homologues to the epidermal adhesion molecules targeted in bullous pemphigoid are found in the brain.11 However, it has not yet been demonstrated whether managing modifiable risk factors for neurologic diseases will lead to lower rates of bullous pemphigoid. With the exception of an often older age of onset, the clinical and immunologic phenotype of bullous pemphigoid arising in patients with neurologic diseases does not appear to differ dramatically from bullous pemphigoid in patients without known neurologic disease.12 From an outcomes perspective, however, presence of underlying neurologic diseases have been associated with higher rates of bullous pemphigoid relapse13 and increased mortality.14

| Previous | Continue |

Case 2

Your afternoon clinic schedule has two back-to-back appointments with chief complaint of “ulcer.” The first patient is a 51-year old female with a past medical history of DMII, previous DVT, hyperlipidemia, BMI >30, and a 25-pack-year smoking history presents with the following ulceration (Figure 2).

Figure 2

The most appropriate next step in her ulcer work-up should include?

- Duplex venous ultrasound

- HgbA1C

- EMG

- Arterial brachial index

- MRI

| Previous | Next |

Correct! Answer:

Rationale

The four most common chronic wounds are diabetic foot ulcers, arterial ulcers, venous insufficiency ulcers, and pressure ulcers. As suggested by the varying etiologies, each type of these chronic ulcers has unique risk factors and clinical features. Venous ulcers, which is the most likely diagnosis for this patient, are associated with increasing age, previous venous thrombosis, higher BMI, physical inactivity, and the number of pregnancies in female patients.15 Typically affecting the medial malleolus and associated with pigment deposition causing surrounding skin dyspigmentation, venous ulcers are reported to account for $14.9 million in annual costs in the United States.16 Use of venous duplex ultrasound provides valuable diagnostic information and allows for visualization of venous flow, valve competency, and potential venous thromboses, and these findings can be utilized in procedural interventions.17 MRI or EMG would be less helpful with this patient’s clinical findings. In contrast to venous ulcers, arterial ulcerations are commonly associated with HTN, smoking, and previous vascular disease and present more commonly on the lateral malleolus with punched-out ulcerations surrounded by atrophic, alopecic skin. In the setting of these clinical findings, arterial brachial index would be useful. Diabetic ulcers are commonly seen on the plantar feet with thickened, calloused skin surrounding, while pressure ulcers frequently overly bony prominences. HbA1c may be important to assess in this patient, but will not provide information helpful in determining the etiology of this patient’s ulcer.

| Previous | Continue |

Case Continued

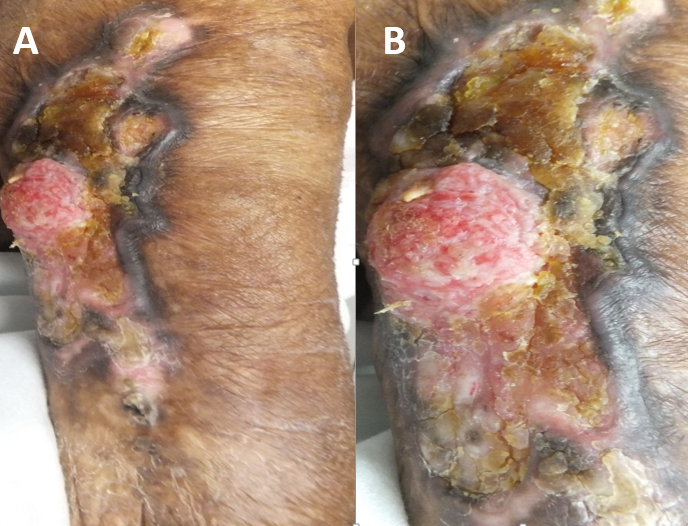

After confirming the diagnosis of a venous ulcer, the patient is lost to follow-up for decades and returns with a persistent, enlarging ulceration (Figure 3). What diagnosis should be ruled out?

Figure 3

- Kaposi sarcoma

- Osteomyelitis

- Pyogenic granuloma

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Bacterial infection

| Previous | Next |

Correct! Answer:

Rationale

Squamous cell carcinoma, and less commonly basal cell carcinoma, developing in the setting of chronic inflammation or wound is known as a Marjolin ulcer. The reported etiology of the chronic inflammation includes burn scars (most common), long-standing venous stasis ulcers, trauma, and primary inflammatory skin diseases including hidradenitis suppurativa and chronic lupus erythematosus.18 This entity, although rare, is a relatively aggressive malignancy with distant metastases at time of diagnosis found in 8% of patients from a recent systematic review of nearly 600 patients.19 The median latency time is frequently reported to be around 30 years,20 and high rates of recurrence are seen.21,22 Clinical features including new nodule formation, induration, and ulceration at a scar site as well as exuberant granulation tissue, rolled margins, and easy bleeding have all been reported as signs of a Marjolin ulcer.

| Previous | Continue |

Case Continued

The second patient is a 59-year old male seen for hospital follow up. The patient has a past medical history notable for ulcerative colitis and was recently admitted for a rapidly progressing ulcer of the lower extremity (Figure 4) of unknown etiology managed with IV antibiotics without notable improvement. He is worried today that the ulcer is “spreading.”

Figure 4

What is the most likely diagnosis?

- Calciphylaxis

- Pyoderma gangrenosum

- Necrotizing fasciitis

- Erythema nodosum

- Herpes simplex virus

| Previous | Next |

Correct! Answer:

Rationale

Classic ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) typically presents as a painful papule or pustule, frequently on the lower extremities, that rapidly ulcerates. Unlike calciphylaxis, which is usually seen in the setting of end-stage renal disease or warfarin use, PG is strongly associated with inflammatory bowel disease (as well as other comorbidities which will be reviewed shortly). Erythema nodosum, while commonly found on the lower extremities in IBD patients, should not ulcerate. Finally, lack of crepitus as well as lack of clinical improvement with antibiotics would favor a diagnosis of PG rather than necrotizing fasciitis.23 As the management of PG differs strongly from many entities in the differential diagnoses, it is important that this condition be considered in the appropriate clinical context.

| Previous | Continue |

Case Continued

What additional comorbidities are commonly associated with this condition?

- Myeloproliferative disorders

- Human immunodeficiency virus

- Inflammatory arthritis

- Type 1 Diabetes

- A and C

| Previous | Next |

Correct! Answer:

Rationale

While inflammatory bowel disease is the most commonly associated systemic disease in PG, additional conditions include inflammatory arthritis, hematologic disorders (myelodysplastic syndrome, myeloproliferative disorders, monoclonal gammopathies), and solid organ malignancies.24 A cohort study of 365 cases found that although clinical presentation did not vary notably by patient age, those < 65 years old are more likely to have concomitant IBD while those >65 were more frequently found to have arthritis, malignancy, or hematologic disorders.25 As PG is traditionally considered a diagnosis of exclusion, the presence or absence of associated comorbidities can be key to making this diagnosis confidently.

| Previous | Continue |

Case Continued

Due to the high clinical suspicion for pyoderma gangrenosum and continued ulcer progression, prompt initiation of which therapy should be considered for both therapeutic and diagnostic purposes?

- Broaden antimicrobial coverage to include antiviral and antifungal agents

- Surgical debridement

- Systemic steroids

- Hyperbaric oxygen

- Colectomy

| Previous | Next |

Correct! Answer:

Rationale

Although consideration of infectious etiologies is important in the differential diagnosis of PG and tissue culture can be considered in this work-up, antimicrobial therapies would not be expected to lead to notable clinical improvement. Additionally, a history of pathergy, or developing new lesions at sites of trauma such as an IV insertion or surgical sites, is seen in approximately 30% of PG patients, and as such, debridement should be avoided while the ulcer remains actively inflamed.26

Although PG is associated with IBD and overlapping treatments exist including anti-TNF therapies, the literature is mixed regarding whether inflammatory bowel disease activity correlates with PG activity.27,28 Although the data is limited, hyperbaric oxygen has been reported as a treatment, albeit frequently adjunctive, for PG in case reports and case series.29,30 However, ulcer improvement in response to immunosuppressive medications such as systemic steroids and cyclosporine is a component of many PG diagnostic criteria31,32 and as such, steroids can be used for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes.

| Previous | Continue |

Case 3

A 63-year old male patient recently diagnosed with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is due to begin treatment in the coming weeks. His oncologist has relayed an intention to start the EGFR inhibitor, Erlotinib, based on her tumor marker prolife. As a longstanding patient, she asks for anticipatory guidance regarding potential side-effects, specifically those which might be visibly apparent.

Which statement is most accurate regarding the patient’s question?

- Mucocutaneous eruptions are uncommonly reported with EGFR inhibitors, and when they do occur, are mild and treatable

- Mucocutaneous eruptions are uncommonly reported with EGFR inhibitors, and when they do occur, are frequently severe necessitating treatment interruption

- Mucocutaneous eruptions are commonly reported with EGFR inhibitors, and pre- emptive management can minimize treatment discontinuation

- Mucocutaneous eruptions are commonly reported with EGFR inhibitors, and frequently necessitate treatment discontinuation

- Mucocutaneous eruptions associated with EGFR inhibitors are frequently localized to mucosal surfaces only

| Previous | Next |

Correct! Answer:

Rationale

The reported incidence of cutaneous adverse events associated with EGFR inhibitors ranges from 50%-90%. Most frequently seen is a pruritic eruption of papules and pustules in a seborrheic distribution which affects more than three-quarters of patients after approximately one to two weeks weeks of therapy.

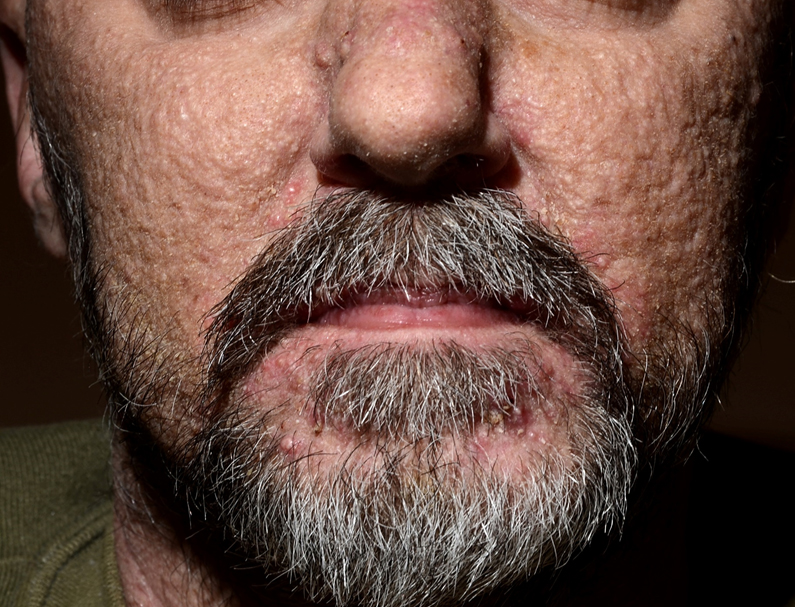

Similar papulopustular eruptions have been seen with multi-targeted receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as dovitinib (Figure 5). While severe eruptions may necessitate treatment interruptions while the reaction becomes controlled, these are fortunately rare and affect <10% of patients.

Other commonly reported cutaneous side effects include photosensitivity, xerosis, mucositis, trichomegaly, and nail changes including paronychia and pyogenic granulomas.33

Figure 5

| Previous | Continue |

Case Continued

What, if any, prognostic implications can be made from the development of this papulopustular eruption in setting of EGFR inhibitor treatment?

- Associated with poor response to treatment

- Associated with good response to treatment

- Associated with subsequent development of severe cutaneous adverse reactions

- Associated with subsequent development of systemic immune related adverse events

- No prognostic implications

| Previous | Next |

Correct! Answer:

Rationale

One of the most important features of the papulopustular eruption triggered by EGFR inhibitors is recognizing its association with an improved response to therapy, regardless of type of underlying malignancy,34 and specifically its correlation with increased progression-free survival and overall survival in NSCLC.35 Therefore, management of this side effect to allow patients to continue on this therapy is crucial, and will be discussed shortly.

Fortunately, EGFR inhibitors are not frequently associated with systemic immune-related adverse events in patients with NSCLC, with the exception of the Osimertinib when used in combination with immune-checkpoint inhibitors.36,37 The prognostic implications of this papulopustular eruption when occurring in patients taking multi-targeted receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors have not yet been fully elucidated.38

| Previous | Continue |

Case Continued

What management recommendations can be made for this patient with a grade I-II eruption?

- Reassurance regarding the positive prognostic implications if this eruption were to develop, and no treatment necessary

- Discontinuation of treatment at eruption onset while awaiting oncology or dermatology input

- Initiating Benzoyl peroxide wash

- Prophylactic oral antibiotics in combination with topical steroids

- High dose systemic steroids (1mg/kg/day)

| Previous | Next |

Correct! Answer:

Rationale

Although anticipatory guidance and reassurance should be provided to patients initiating this therapy, prophylactic treatment is often also recommended. Preventative measures include: Avoid over-the-counter acne medications, such as Benzoyl peroxide, which may increase irritation and start a six-week course of oral tetracycline antibiotics along with a low-strength topical steroid like 2.5% hydrocortisone to the face twice daily at the start of treatment.39

A phase II clinical trial looking at preemptive versus reactive treatment of skin toxicities with the EGFR inhibitor, Panitumumab, found that the preemptive group had a greater than 50% reduction in the incidence of grade 2+ skin toxicities compared with the reactive group, less quality-of-life impairment, and less patients affected by EGFR dose delays.40 Grade III-IV eruptions (>30% BSA affected) often necessitate temporary treatment interruptions until severity has decreased, and testing for superinfection of affected areas is recommended.41

In addition to the recommendations for grade I-II reactions, systemic steroids and low dose oral retinoids can be considered for these more severe eruptions according to guidelines published by the European Society for Medical Oncology and the Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer.42,43 Additionally, as EGFR inhibitors are employed against an increasing number of malignancies, including colorectal carcinoma, concern regarding the potential clinical impact of tetracyclines on the gastrointestinal microbiome has been raised.44 These patients may benefit from an alternative systemic therapy for EGFR associated acneiform eruptions, and growing evidence suggests oral retinoids, specifically isotretinoin, could be of benefit.45

| Previous | Continue |

Case 4

A 44-year old male with a family history of psoriasis and no notable personal medical history presents for evaluation of minimally pruritic, well defined scaly plaques (Figure 6).

Figure 6

Presence of a positive family history of psoriasis is associated with what clinical feature(s) related to development of psoriasis?

- Male gender

- Earlier age of onset

- Less severe disease

- More frequent enthesitis

- B and D

| Previous | Next |

Correct! Answer:

Rationale

The cutaneous lesions this patient has developed are consistent with psoriasis. The etiology of psoriasis is multifactorial, including a complicated genetic component as demonstrated by concordance rates in twin studies and HLA associations in population-based studies. Specifically, HLA-Cw6 is strongly linked to psoriasis.

Although there is variability in the reported rates of family history in psoriasis, a study of over 3500 families reported the lifetime risk of psoriasis to be 0.04, 0.28 and 0.65 if no parent, one parent or both parents had psoriasis, respectively.46 Furthermore, multiple cutaneous and musculoskeletal features are linked to a family history of psoriasis. These features include female sex, plaque psoriasis phenotype, earlier age of onset, and increased risk of nail disease and enthesitis.47

| Previous | Continue |

Case Continued

What cutaneous site of involvement is less commonly associated with plaque psoriasis?

- Antecubital fossa

- Scalp

- Elbows

- Umbilicus

- Lumbosacral area

| Previous | Next |

Correct! Answer:

Rationale

Chronic plaque psoriasis, the most common phenotype, is characterized by well-demarcated erythematous to pink papules or plaques with overlying adherent silvery scale.48 Although the erythema may be more subtle in people (or patients) of color, subsequent dyspigmentation is more common.49 Typical areas of involvement include scalp, extensor surfaces including elbows and knees, umbilicus, lumbosacral region and gluteal cleft. Flexural surfaces, such as the antecubital and popliteal fossae, are more commonly affected in atopic dermatitis and less frequently involved in plaque psoriasis. Morphologic psoriasis variants include guttate psoriasis, consisting of smaller and thinner papules and plaques, and inverse psoriasis, which affects flexural areas like the axillary vaults.

| Previous | Continue |

Case Continued

At the patient’s follow-up visit several months later he endorses morning joint pain in his hands on review of systems. Which of the following most accurately describes the onset of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis?

- Arthritis typically precedes skin lesions

- Cutaneous lesions and arthritis typically develop concomitantly

- Cutaneous findings typically precede arthritis

- No clear pattern reported in literature

| Previous | Next |

Correct! Answer:

Rationale

Reported rates of psoriatic arthritis in psoriasis patients range from 6%-48%, with more frequently cited rates of ~30%. Recognizing psoriatic arthritis is crucial, as joint inflammation can result in irreversible destruction, unlike the cutaneous findings.

Furthermore, a cross-sectional study from 2016 estimated around one-half of patients with psoriatic arthritis in primary care are undiagnosed.50 While small percentages of patients have joint involvement preceding skin involvement (approximately 15%) or develop symptoms concomitantly (10%),51 the majority of patients develop cutaneous psoriasis prior to joint activity, and typically within the first 10 years of diagnosis.52

| Previous |